Sława and Izydor Wołosiański

Whenever Sława was asked - "Why did you save Jews" she answered: Me? Jews? No, I did not save Jews, I saved people, friends, acquaintances.

Sława and Izydor Wołosiański saved 39 Jews during the Second World War. Poland was the only country in Europe where there was death penalty for helping Jews. Despite that Sława and Izydor were hiding 39 people in the basement of their house for almost two years. One of their neighbours was German."You were 24 years old, weren't you afraid?" What is there to be afraid of? If you can only kill a person once, how can you kill them 39 times? It's easy to say. Her story is in each generation of us, we are Sława."

Why Sława?

Born in Borysław on February 9, 1919, as the second child of Ewa and Jarosław Skolski, when asked about her name she always replied - Who the hell gives a girl a name after her father! Some kind of nightmare. Her older brother Zbyszek, when the war broke out fled home and joined the Anders army and never returned to Poland. To the communist one he did not want. Two years younger sister Danusia, is alive and still lives in Otwock. Sława had a major visual defect from childhood, they called her Blind Tiutia or Kubuś.

Brave. The word fear found no place in her vocabulary

The choices this young girl made with her future husband Izek set the trajectory of our lives, took away our fear of the unknown, and were the seeds of the courage that shaped us.

At just eight years old, she came to her dad and said she wouldn't go to religion because she didn't like the priest and... she didn't go.

Dying almost in our arms in December 2006, she told me and my husband Peter that she was not afraid of anything and that we should not cancel the wedding and reception planned for January, because she wanted it that way and that's it. She was always determined, even in the last moments of her life.

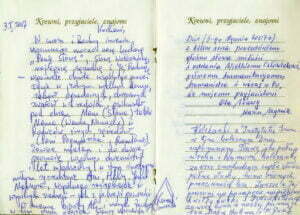

See how Sława describes her story

This is how she herself describes the events of the war

I was born on February 9, 1919 in Borysław, but I went to school already in Drohobych

In 1937 I passed my high school diploma, I was living with my parents at the time, my sister was still going to school. The war found me in Gdynia. Literally on the last day of August I was returning home. My brother Zbyszek went to war and never returned to Poland. He was in German captivity, and we first survived the Soviet occupation in a terrible way, we could not get used to them. You couldn't even go out on the street. In 1941 the German-Russian war broke out, which found me not in Drohobych, but in Lviv. I went to a friend's wedding, but before I arrived by train it was already over. Lviv was bombed. It wasn't very bombed, but we saw a bombed tram. It was terrible. The Russians, retreating, murdered everyone. I saw the humiliation of the Jews, who had to carry these corpses away, beaten with butts, tugged, kicked and shot in the streets if any behaved not as the Germans wanted. I wanted to return home as soon as possible, but it was impossible to escape from the horror of this war anywhere.

One of the first moments that made a terrible impression on me took place on my street. I was returning from a friend's place when suddenly I saw a German soldier throwing a tiny child onto a truck bed, while the mother with another child at her breast tried to climb onto that truck. After coming back home, I cried terribly and couldn't calm down for a long time.

The next day, my sister and I went to the city and saw a girl who was talking to her reflection in a window, saying, 'You didn't want to eat bread with butter, and now you're eating the crusts and enjoying them.' On our way back home, we saw a gathering of people. It turned out that because they were going to take the Jews from our street, the whole family poisoned themselves to avoid falling into the hands of the Germans.

Sława in the first grade of elementary school in Drohobych

(second row from the bottom, first from the right a girl, wearing a white blouse)

The story of Fame and Isidore

At the same time, at my friend's house, I met my future husband, who was friends with her much older brother. My husband was 11 years older than me, and he introduced me to his Jewish friends. They gathered on Szaszkiewicza Street, at the home of his two Zajfert friends. There I met most of the people we later rescued by storing them in the basement. Among them was a two- or three-year-old girl named Ania Lindt. Her parents, when they could hide somewhere, asked me to take the little one in. She referred to herself as "red as a tomato, red as a carrot." In fact, along our street, Germans were walking through the houses - two at a time - looking for Jews. I asked my mother and sister to leave the house, and I simply put Ania in the window. I thought that the Germans would not be suspicious of putting a Jewish child in the window.

I was also slightly red-haired at the time, and Anna could pretend to be my child. That's how she saved herself. We rescued her several more times. She was the youngest child in our basement. In 1942 a ghetto was established in Drohobych. Unfortunately, no schoolmate, I did not manage to save. One did get saved, but regardless of my actions.

Together with Izydor Wołosiański in 1942 we started to help. When there was an action, he would take the Jews to the basement in the workshop where he worked. Together we brought them food for two, sometimes three days. I would wait in the courtyard, and Izek would carry food to them. When the ghetto was established, people who didn't want to go to the ghetto or couldn't because it was known that they would be killed right away - that is, children and the elderly - decided to hide in a hiding place that one of the Jewish families had prepared for themselves. The owners of this house at 9 Szaszkiewicza Street were the Zajfert family. With the help of Mr. Sztok, who was a parquet worker, carpenter and a very good craftsman, they built a hiding place. It was supposed to hide Mr. Sztok with his wife, two children and a nanny, as well as the Zajfert family. They arranged for the youngsters to get false Aryan papers so they could leave. The elder Mr. and Mrs. Zajfert went to the ghetto and died there. Hiding in the hiding place was Zajfert's sister, Mrs. Hendlowa, who worked as an accountant. She still hid her daughter and her husband, who did not speak Polish at all. Mr. Sztok hid his two daughters and his housekeeper. Also hiding was Mrs. Rosenberg, who also did not want to go to the ghetto, and her daughter Hela, who witnessed the execution of her father by the Germans.

In the building where the hiding place was located lived with his housekeeper, the German treuhander (trustee) Herzer. For us, this was a favorable circumstance, since the Germans were unlikely to look for Jews in houses where Germans lived. Mrs. Hendlowa was supposed to go to the ghetto every day, but she did not do so and slept in our apartment. She used the bathroom and had her own corner in our house, and above all she could contact her husband and daughter, who were in the basement. The exit to the basement was in our apartment between the office and the kitchen. However, it was very dangerous. I had this entrance killed and made an entrance in the kitchen floor. This was done by Mr. Sztok, at the time he and his wife were still working and only occasionally used the hiding place. If they managed to get something to eat, they brought it to us, but the main food was brought by us. At the time, one German wanted to move into their apartment. Herzer from the second floor was very uncomfortable with this. He suggested to my husband that he bring his father Mikołaj and his daughter Stefa to this apartment. Since they could not be brought in, we decided to get married and occupy this apartment. On the day of our wedding, January 6, 1943, there were already 14 people in the hideout.

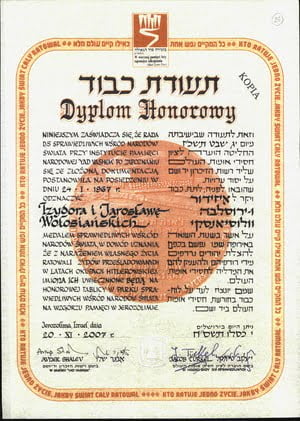

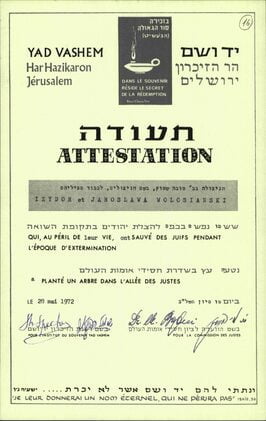

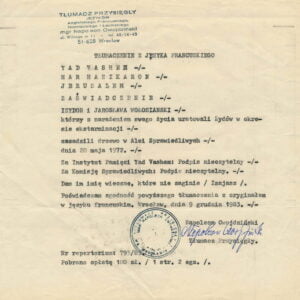

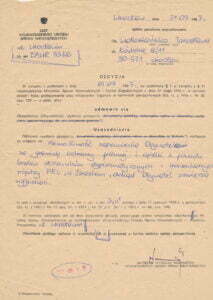

Medal presentation at Yad Vashem

More and more people were seeking refuge, but the cellar remained the same

14 people is an army of people, I shopped every day in a different store, no one knew me, before that the household was run by my mother Ewa Skolska - so no one knew how many people I had to feed. Even when someone knew me, I would say that I was shopping for my parents or for a friend, who parenthetically speaking - stored at her workplace - 18 Jews. My husband would go to the train station and, if he could, buy groats and flour from the traders. From the train station to us was about 3.5 kilometers so there and back he would go by cab. Everyone was stocking up, so no one was surprised by the larger purchases. I tried to make sure no one saw my supplies, which were languishing in the basement that same day.

There was gas and light in the basement - they could cook there - but the big cooking was mostly done in our kitchen. Those in hiding slept during the day. At night they started living, washing, eating because then no one could hear them. We were not afraid of the German, I was on great terms with him, he spoke excellent Polish, he came from Tarnowskie Góry. He told me that his mistress was afraid because the partisans were near Drohobych. He did not harass me and my husband, but he kicked the caretaker for opening the gate too late, so that the caretaker died. He also turned over to the camp the man who took care of his horse. He rode his horse every day, and led this man to the ghetto execution site at Dachówczarnia. No one realized that there were people in our basement. If anyone had realized, we would have been gone. Even my parents and sister Danusia didn't know, only a schoolmate who had the same problem on her mind as we did. Sometimes we helped each other. She, when she had more food and couldn't deliver it to her "charges," would bring it to us. I, in turn, covered for her. When the lady came with milk, I said I was taking it for my friend, where there were five of them at home. During the occupation it was hard to get food, but we survived and no one died of hunger.

Still living in the same house on Aryan papers was Mrs. Halina Ekierska - a Jewess - with her husband, who was seriously ill with tuberculosis. She worked in the position previously held by Mrs. Hendlowa. I suspected that someone was still with her, because at night I heard a terrible cough. She confessed to us that she was with her husband, Izek took him to the doctor, but it was too late to help him. At a critical moment, I called the doctor to come to the child. She could no longer help him, she said it was a matter of hours maybe one day. In fact, he died. Mrs. Ekierska threw us the keys and went away saying: "Bury him!" She returned three days later and took her things. I didn't see her again. She survived because people saw her after the war. The night we buried Mrs. Ekierska's husband was terrible.

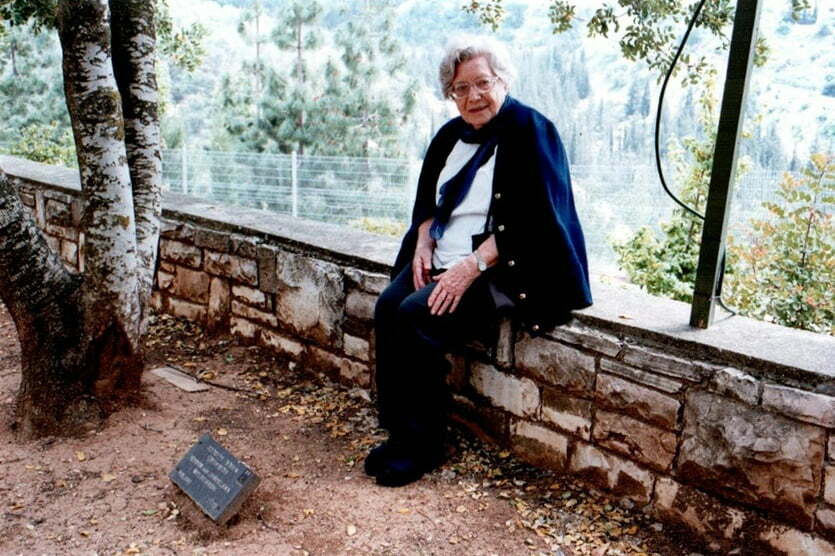

Sława at Yad Vashem by her tree in the Avenue of the Righteous

Into the world comes a consolation

In the meantime, my husband would go out into town. Every now and then he would come back with a crestfallen look, and I knew that we would have new people. We had to inform those downstairs to prepare a new place, which meant digging the ground and burying it between the two floors. There was only 25 centimeters between our floor and the technical floor, where they dumped the soil from the new cell for the next occupants. It wasn't high, adults couldn't stand up straight, and young children could only stand with difficulty - they had to lie down. We had a lot of books, and I tried to give them something to read. The ladies did some handiwork, sewing, read a lot, played cards, and argued over them. One of them, known as the captain, who thought he was the master of life and death, came up to me and said, "Sława, I've sentenced Dziumka to death." He was an older man, about the age of my mother. I replied, "Sir, I'm saving you from death, and you're telling me that you've sentenced someone to death? How do you plan to carry out this sentence?" Of course, nothing happened to anyone; he was a bit of a "loose cannon." Once the ladies had a quarrel and poured water on each other. It was difficult to endure in such cramped quarters. I went downstairs occasionally, but my husband went down more often and played cards with them. I did so less frequently. At first, I was pregnant, then I took care of the child.

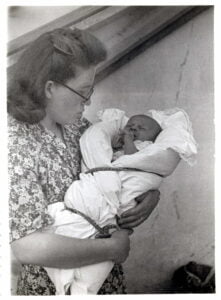

In such conditions, on August 4, 1943, my daughter was born, at which time there were already about 30 people with us.

There was no sewage system in the basement, buckets of waste had to be removed, water had to be carried in. It was terrible, because my husband had to walk down a narrow corridor several meters, and at night someone could see him leaving with the buckets and entering the basement. I told him, let them dig and dig into those of ours. They were on the same line, they were under the kitchen and that other group was under the dining room. I said, let them dig. Those there didn't know, and we didn't have the guts to tell them that they would get another 5 people in a moment. They dug in, it was the surprise of one and the other, those who dug, that they had light, gas, water and so many people. And those there, that someone dug in. That's how the 39 people compiled. And it seems they were the last. That's how we had to live on.

It went on and on, every day and every moment brought danger. Yes, but a person gets used to certain situations. When nothing bad was happening, they were not looking for Jews in the city, I sang lullabies to my daughter. They knew that when I sang it was all good. If I didn't sing, they were concerned.

We lived like this, until I learned that one of the ladies was pregnant. We began to wait, the Russians were already near Ternopil at that time, the front had stopped, however. The woman who was pregnant gave birth to a child. Unfortunately, it was dead, it was buried between two floors. There were three doctors in the basement, she gave birth naturally, without any complications.

Willingness to help above all else.

Some time after this incident, I learned that my best friend Hela, whom I met during the war, was also about to give birth, and in fact I learned about it after she had already given birth. Unfortunately, she gave birth, the placenta did not come off, she was seriously ill, she went blind. I asked the doctors in hiding at the time, including Dr. Miszla, to operate on her. They replied that they did not have the tools, I offered to get them, but they still refused to operate. I remembered that there was a man named Watenrot, who by virtue of his occupation - he was a gardener - has good contacts with the Germans and might be able to help. I called him and made an appointment. I said it was about a friend of mine who had come out of the woods, given birth to a child and needed to be operated on. He arranged everything. At the last minute the doctor chickened out and told her to go home. With the last of her strength she reached us. I, meanwhile, drove Anya to my mother. I always did this in dangerous situations. When I returned, I found Hela unconscious on the doorstep of our house. We were sure that this was the end of us all. The caretaker saw her, she was in the hospital, then "our" doctors made a consultation and told us to leave the house and leave them to their fate. We said that this was out of the question. I couldn't imagine the Germans coming and dragging 39 people, including seven children, out of the basement. We said it was out of the question and we stayed. The treatment was carried out, Hela regained her sight after several days.

Years later, Hela gave birth to a son, Jurek, unfortunately, after the death of her husband - many years after the war - she could not live without him and committed suicide. There was war in them. Jurek does not keep in touch with us, I have at home his English books and his ski pants, the most beautiful in the world despite the fact that men's....

June 1943, we were waiting for the approaching front. The Germans began to flee, one time I went shopping with my friend Staszka, with whom I was friends at the time, we had something in common, German tanks were driving and there was something attached to them. I say, "What is this, are they sleeping in these tanks?" and suddenly a man in a German uniform speaks up and says in fluent Polish - "This is how heroes return from the front." I came into contact with this man as I was working in an iron foundry.

For a while I worked there - until the fourth or fifth month of pregnancy - then I stopped. Already after the war it turned out that it was a Pole - a spy from Drohobych. Working in the foundry, at the request of my husband, I gave Auswaisses, such certificates that they work. I don't know how many of them I issued, everywhere I signed my maiden name - Skolska.

Whenever we came home we came first to the chancellery, where Mrs. Hendlowa was waiting for us to tell us if anything had happened. Once she informed me that there was a gentleman in the uniform of a Field-German waiting for me, I shuddered.

Sława with grandchildren rescued

"Does your maiden name happen to be Skolska and your married name Wołosiańska?"

Does your maiden name happen to be Skolska and your married name Wołosiańska?

I answered - yes. We will not talk here, he says to me in German, let's talk in your apartment. As we entered the apartment, he says in the purest Polish, that he was dropped as a cichociemny and has a task to perform in Drohobych. At the time, Drohobych was home to the largest Polmin oil refinery, it seems, even in Europe. He was to prepare a plan for the bombing of Polmin. He was an engineer by training and a friend of my husband's brother (Alexander Wołosiański), they worked together at an aircraft factory in Lublin. His only request to me was that I hide his briefcase with documents somewhere.

In addition to a hiding place with people, we still had a hiding place under the couch, and that's where I hid his briefcase. He was supposed to come back for it in two weeks. He also told me how he got to me. Well, while inspecting people riding the train he met a woman who was holding a document signed by me, he asked who had given her the document, and she confirmed that Volosianskaya had given it to her. He was friends with my husband's brother, with whom they went through the entire war campaign and got separated in France. My husband's brother went to Morocco and he went to England. He was dropped several times, I don't remember his name, but his name was Stefan. He came on Tuesday, already in civilian clothes. He said that on Wednesday next week we should listen to BBC radio, there would be greetings from Stefan. In fact, there were. I thought this was the end of the story, and yet not, as we were already living in Wrocław, I was returning with my daughter from a walk and the housekeeper says to me that a gentleman is waiting for me. I walk in, and there is actually a man waiting, and he asks: "Don't you recognize Stefan?" He did not live in Wrocław, he found us.

There were many other adventures. My husband and I did not belong to any organization, because I do not like a regime over me. We had our own private organization and our own regime.

One may ask the question "What were the motives behind this action - pure humanism and kindness to people?" However, day after day, we and those people who hid in our basement were threatened - the death penalty.

At the beginning, when we decided to do it, there were 7 people in our hiding place, what was I supposed to tell them - get out? And watch them being shot or find out that they shot them in the nearest street or in Bronica, where the main execution site was located. It was about 6-7 kilometers from Drohobych, the forest where the Jews were shot. One day a woman came, a very good friend of my husband, who crawled out from under a pile of dead people, all bloody and in the mud, woke us up in the morning - maybe it was five or four in the morning. We wanted to hide her with us, but she didn't want to. She said she had Aryan papers and was on her way to Lviv, only she was caught unexpectedly somehow. She only asked to be allowed to bathe and change her clothes. I don't know what happened to her next, whether she survived. We never heard from her again.

Sława with the Sztok family

What was a normal day like?

Once it started, we had to go on, there was no turning back, unless to condemn ourselves to eternal remorse. Maybe it would work and we would give it up. We had only one rule, we would never take money for it. Not a penny. It has to be selfless, otherwise it has to fall apart.

Confirmation of these words is one sentence in Henryk Grynberg's book "Drohobych, Drohobych" ....

Once my friend, who also helped people, came to me, she told us that there is one jeweler from Lviv who gives a bag of diamonds for hiding but I told her then: "Stasiu, don't be angry, but let him look for someone else for these diamonds" There were already 39 people with us at that time. There was really no room especially since he suffered from claustrophobia, I had nowhere to hide him. In the apartment I would endanger others. Anyway, I didn't want money, I didn't want anything. I wanted to give people and myself life. I also wanted to save myself.

What did each normal day look like?

I was at home, my husband was working, I went out often to go shopping. Our house on Szaszkiewicza Street was at the intersection of Grunwaldzka Street. Every time I came back, I looked to see if there was a confluence on our street. I checked to see if something had happened, maybe these people were being taken away. If nothing happened I would return home quietly. I would bring food. I drank something and went back to shopping, and so on all day. When the baby was born, I would walk with the baby, all the time going back and forth to buy food. Drohobych was a sprawling city. From the end to the end of the city was about 6 km, there were a lot of stores, of course, there were not some luxury goods. Later the problem began, some people no longer had money. It was necessary to force the others to bear on these others, some rebelled, but I said quite sharply - "it's difficult everyone must survive, they can not die of hunger". And so they saved themselves. This went on for 22 months - from September 1942 to August 1944.

On August 04, 1944, as my daughter Ania turned a year old, on her first birthday, the Russians entered Drohobych with a big bang.

Sława and Izydor Wołosiański Gallery

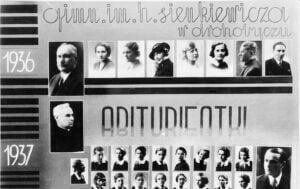

1. Sława in Drohobych gymnasium

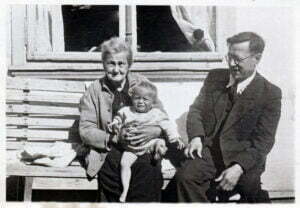

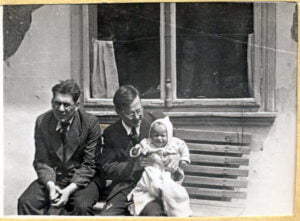

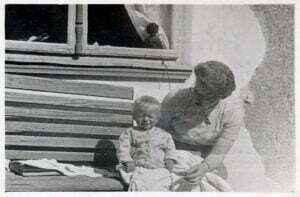

2. Mikołaj Wołosiański, Ludwika Shmidt in front of the house at 9 Szaszkiewicza Street with Anna

Mikołaj Wołosiański with Izek and Anna in front of their house in Drohobych

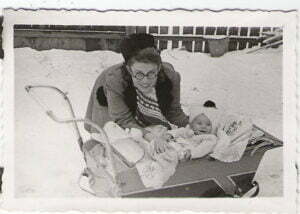

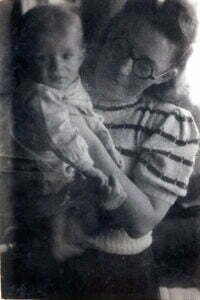

4. Sława Wołosiańska with Anna winter 1943, Drohobych

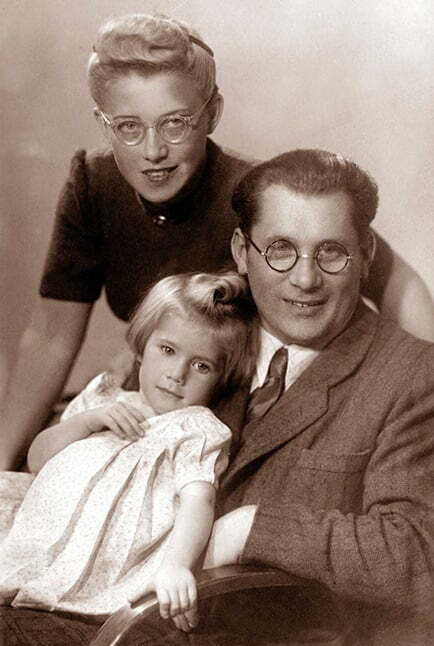

5 Anne and Henry Milgrom, Wrocław 1949

6. Anna, Izek, Sława

7 Anna, Sława

Ania before leaving for Wrocław, Drohobych 1946

9. Anna Wołosiańska, Drohobych

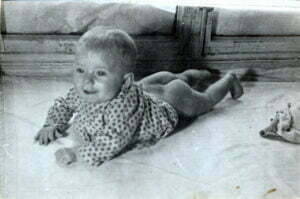

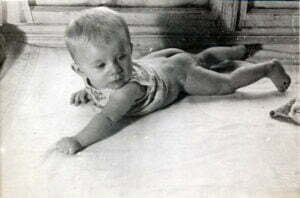

10th Anna Wołosiańska, August 1944

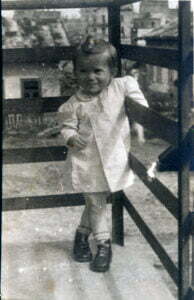

11. Anna Wołosiańska Drohobych, autumn 1943

12. Anna Wołosiańska Drohobych, spring 1943

13. Anna Wołosiańska, winter 1943, Drohobych

14. Anna Wołosiańska with Sława, spring 1944, Drohobych

15. Anna with Sława, Christmas 1943 Drohobych

16. Sława and Ania 1943

17. Sława with Kasia Skopiec

18. Sława with the youth of the Edith Stein Society, on the right Wiktoria Miller

19 Anna and Sława Israel

20. fame in front of the house

21. Sława meeting with Szewach Weiss

22. photos of Abiturients 1937

How You Can Help

Support the work of our Foundation in cultivating the memory of the Righteous - only with your help can we succeed!

The founders of the foundation have been actively helping refugees for more than 15 years. Humanosh Foundation has been operating since 2020, with the help of the family, volunteers and thanks to the support of donors we help refugees and spread the story of the Wołosiański family.

Our mission is to build a reality in which every person feels safe and dignified. regardless of their background, race, religion or skin color.

Only with your help can we succeed!

](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ars_logo1-photoutils.com1_.jpg)

](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/CU-marketing-consulting-photoutils.com1_.png)

![ELEOS [photoutils.com].](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ELEOS-photoutils.com_.png)

![FOR_Logo_Horizontal [photoutils.com].](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/FOR_Logo_Horizontal-photoutils.com_.png)

![Citizenship Fund [photoutils.com].](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Fundusz-obywatelski-photoutils.com_.jpg)

![GCF-logo-pdf-for-banners [photoutils.com].](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/GCF-logo-pdf-for-banners-photoutils.com_.jpg)

![Ilios [photoutils.com].](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Ilios-photoutils.com_.png)

![Logo_National_Forum [photoutils.com].](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Logo_Krajowe_Forum-photoutils.com_.png)

![Neuca-1 [photoutils.com].](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Neuca-1-photoutils.com_.png)

![Orlen [photoutils.com].](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Orlen-photoutils.com_.png)

](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/SGH-photoutils.com2_.png)

![WUM-1 [photoutils.com].](https://humanosh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/WUM-1-photoutils.com_.png)